I’d never heard of Bilwinowo, Poland, until a few months ago. This tiny village has provided the most significant piece in the scattered genealogical puzzle pieces my father and his mother left behind.

Growing up in a quiet suburb sixteen miles west of downtown Cleveland, my childhood was idyllic. One of my favorite places was my Grandma Hill’s backyard. I adored her apple tree. It was the only tree I was able to climb.

Look at that kid. Why would that little girl want to know about the ramshackle Polish village where her great-grandfather was born? The thing is, I was very curious about family history. Even then. I liked hearing my Grandpa Malloy reminisce about my mother’s Irish ancestors. Grandma Hill had to have some of her own. More than once I’d heard her speak fondly of her dad, always ending with his most famous quote. “I’m the wealthiest man in the world! I’ve invested my future in seven different banks – my children!” If one of her grandchildren pushed for more information, she described him like a Disney character. He was a prince, humble and wise, from an aristocratic family somewhere in Europe. He loved to read to his children, and he valued education. He was a respected businessman in Berea, Ohio. No, he wasn’t Polish. Maybe Russian. Maybe German. Maybe Hungarian. But that’s not important. According to Grandma, we were 100 % American.

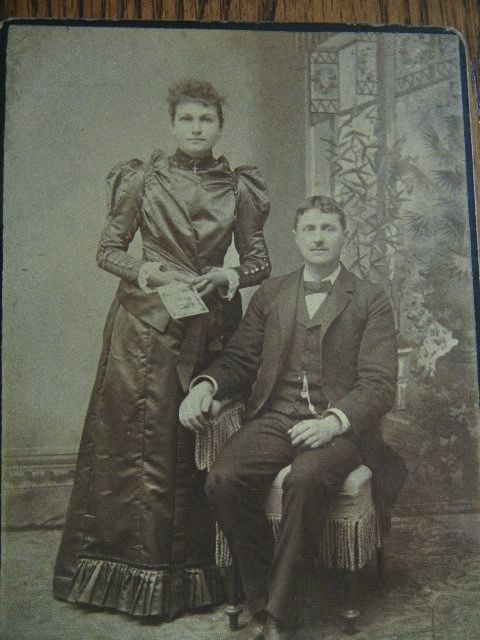

Grandma Hill’s parents:

Pelagia Szweda and Jan Dziedzikowski, 1892. The paper in her hand is their marriage license. This is the type of photo Polish immigrants sent back home to announce a marriage.

My grandmother, Harriet Doskey Hill, was the primary author of the fairy tale otherwise known as my childhood. Dated 1927, my father’s birth certificate was its first sentence: Myron John Hill, born, son of Joseph F. Hill and Harriet Doskey Hill. They’d been married ten years, without a child of their own. His birth provides the earliest example of them using their chosen Anglicized name on a legal document. In the records of St. Ignatius Church, their 1917 marriage is recorded under the names Jadwiga Doski and Jozef Gorzynski. Joe was a widower then, with a son named Frank. After they married, Hattie and Joe and Frank lived in the Gorzynski family house in Cleveland’s Warsawa neighborhood. My father’s birth was probably the reason for leaving the family behind. Jadwiga and Jozef re-created themselves as the All-American Hill family. Even Frank became a Hill before he ran away to join a carnival.

During the depression, Hattie and Joe signed loan papers for the unfinished shell of a foreclosed house in a rural Cleveland west-side village called Fairview. They succeeded in paying it off in six months. Buying this house provided them with a place to raise Myron HIll as a pure, unhyphenated American.

My grandmother’s penchant for changing names even extended to the dead. My father’s name, Myron, gestured towards the Polish tradition of naming a first-born son after his paternal grandfather. To secure her side of the story, she had it etched in stone: on my great-grandfather’s gravestone, his name is Myron Gorzynski. Judging by the age of the stone and the carving, it was placed there in the mid-1950’s, after grandpa’s sister Helen filled the plot. Gorzynskis had been dying since 1910, and I’m guessing an earlier, more honest, stone marked the spot. Great-Grandpa’s baptized name was Marian.

You’ll note grandpa’s sister Helen’s surname is Doskey. My grandfather’s sister Helen married grandma’s brother Clem. For the first few years of their respective marriages, they all lived together in the Gorzynski house, along with the matriarch, Frances (Franciszka) Gorzynski. Helen had a girl named Delma a few years before Hattie had Myron. Ultimately, both couples struck out on their own, leaving great-grandma Franciszka alone in a three family triplex. Censuses tell me she was illiterate and didn’t speak English.

When I first saw this grave, I wondered if the stone was upside down. Or was the tree purposefully planted on top of the coffins? If so, did a Gorzynski plant it? Why? One thing’s for certain, once you’ve found the Gorzynski grave at Calvary Cemetery, you’ll always know where it is.

I suspect there was a feud between Hattie Hill and Helen Gorzynski-Doskey, and perhaps it was over the idea of changing a dead man’s given name. As the one who died last, my grandmother won. Taking control over the headstone, she altered details to her liking. Remarkably, she didn’t change the Gorzynksi surname. I like to think my grandfather refused to let her go that far in erasing his family’s memory.

My grandmother’s preserved receipts for “debts fulfilled” reveal a story of cemeteries. She paid for many headstones and their engravings, including her own. Except for the Gorzynski stone, they’re all located in the Doskey family plot in Holy Cross, Cleveland’s west side Catholic cemetery. Grandma even paid to exhume her father’s remains from the Polish section at Calvary and move him fourteen miles to his new resting place. The last time I visited Holy Cross, I couldn’t find any of them. I recognized names on some of the better-maintained graves in what I thought was their section, but the earth had all but consumed unattended grave-markers. I dug out a few, but found other names. I uncovered as many as I could until I lost heart. After all, I’d only stopped for a moment or two to visit my parents’ grave, before heading back to my home in Buffalo. I hadn’t any proper tools for unearthing headstones. Maybe another time. A warmer day. Luckily, I’ve seen the Doskey monuments before. The largest one memorializes John and Pauline Doskey, grandmas’s parents; the second largest is Harriet herself, beside her husband, Joseph Hill. Her younger brother Frank and his wife Irene are there too. Her sisters, Irene and Charlotte, lie nearby, as does brother Clarence, eternally estranged from his wife.

One night, only a year or two before she died, Grandma and I were alone together, drinking tea and talking. Again, I asked about my family’s Polish heritage. This time, she gave in. Sitting close beside me, she took my hand, and told a story about her father. He was the son of a Polish aristocratic family who lived on a forest estate in an area that was occupied by Russia. Their fortune was invested in lumber. One day, her dad was given a load of wood to deliver to the harbor and told to get a good price, take the money, and build a future in America. Here’s a modified version of this story from a letter my grandmother sent to my father’s cousin, Jack. He made sure I had a copy before he died. Here’s the important page:

Lucky Jack. He got the names she withheld from me. Suwałki. Dziedzikowski. But Jack was a historian by training, and a Doskey. She probably figured he deserved to know. I was a Hill, with an Irish mother. (My grandmother opposed her son’s marriage to a girl with my mother’s working-class Irish upbringing.)

When I gave the information from Jack’s letter to genealogist Iwona Dakiniewicz, her first reply was that Dziedzikowski was a ridiculous name. It was the kind of name peasants made up in America, so folks would think they’re aristocracy. She thought his name was really Dziedziach. Channeling my grandmother’s stubbornness, I told her I only wanted Dziedikowski records. She sent me a few.

Several years have passed since that research, and I’ve given in. Iwona was right. My great-grandfather’s name was really Dziedziach. In 2020, a DNA 3rd cousin who shared Doskey cousins with me appeared on Ancestry. His surname was Jessick. When I wrote to him, he told me his grandfather changed the family name from Dziedziach. Oh, how I admire this distant cousin’s style! The sound of “Jessick” is very close to the the Polish pronunciation of Dziedziach. With this varification, I turned to the Polish genealogy database Geneteka, and found the births of both my great-grandfather Jan and his brother, Stanislaus, who immigrated with him. In America, they both used the name Dziedzikowski and the pseudonym Doski or Doskey. When he died, great-grandpa’s name was given as John Doskey, and his father’s name given as Peter. Here’s the citation I found at Geneteka:

So, it would appear part of Jan Dziedzikowksi’s tale was true. His father’s name was Peter – Peter Dziedziach, and his mother had a name, too. Cesaria Mackiewicz. In the screen shot above,”Vesicle” indicates the Parish he was baptised in; Bilwinowo, the town of his birth. Through this database, I’ve traced two further generations back, discovering more ancestral names, both Polish and Lithuanian: Gieryk, Zdanowicz, and Sustkowki; Domalewski and Wyszenki. I traced each family back into the days of the Commonwealth. All lived in and around Bilwinowo. Notably, Bilwinowo is near Suwałki, as my grandmother said. Researching the greater Suwalki area during World War II, I watched the film “Legacy of Jedwabne” which documented those who remained in that village after the 1941 pogrom there. An interview near the end stopped me cold. It was with a man who, with his brother, cleaned up the remains of his incinerated Jewish neighbors. His surname was Dziedziech.

Bilwinowo is 132 km north-east of Jedwabne. Google Translate helped me read a Polish language wikipedia entry that calls my great-grandpa’s birthplace “The royal village of the Grodno economy.” This “royal village” designation harkens back to the Commonwealth days, when Bilwinowo was “within the Grodno district of the Trakai Voivodeship ” “A characteristic feature of the Grodno district was the predominance of royal property over noble property, with a negligible share of clerical property. Within the Grodno district there were staroties: Filipów, Przewalski, Przerośl, Wasilków and smaller royal estates.” Bilwinowo was one of them. During the Polish Partition, as Russia tightened its control over the area, former Polish aristocrats or royals who lingered risked deportation, or worse. Geneteka tells me my 2X great-grandpa Peter died two years after his sons left for America. A year after his death, widowed Cesaria remarried Leonard Tylenda, and had a daughter. I’ve found some records in northern Michigan that suggest they came to America.

North-east of Suwalki, Bilwinowo is located in a borderland region known as the Suwałki Gap . Some consider this to be the most dangerous place on earth right now. “Stretching about 100 kilometers along the Lithuanian-Polish frontier, between Belarus in the east and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad to the west, Western military planners warn the area would likely be one of the Russian president’s first targets were he ever to choose to escalate the war in Ukraine into a kinetic confrontation with NATO.” (Politico). Some think the third world war could ignite in the Suwalki Gap.

So, I don’t plan to visit there anytime soon. Luckily, the internet has informed me a little about Bilwinowo. From above, it looks like this:

Walking down that road, a visitor there would come across the crosses. It appears that Bilwinowo is famous for the crosses people have erected there, memorializing what stood, long ago.

This photo is taken from a Polish blog page titled “Bilwinowo“, which features many photos of the memorial crosses erected there. Again, I used Google Translate to read the account of these monuments. Here’s what it said:

Another cross is located in the center of the village, next to the recently built chapel commemorating 220 years of the existence of the village of Bilwinowo. There is an inscription on it:

“Less of us in your care – a souvenir of the village of Bilwinowo.”

This is where May services are held. Almost the entire village gathers and at 7 p.m. a litany to Our Lady of Loreto is recited, and later songs are sung in honor of Mary.

This cross was made a long, long time ago and, like other crosses, it was initially made of wood, and in July 1986 it was made of gravel.

So, my great-grandfather’s tale of noble ancestry have some truth to it. However, evidence of his family’s fortune in the homeland has been destroyed by one hundred and fifty years of occupation and war.

Still, people live there. Not many. Stalwart types, I imagine. Survivors. Former royalty or nobility?

My Great Grandpa Jan Dziedziach/Dziedzikowski/Doskey, was a survivor, too. He operated a successful grocery store in Berea, Ohio for over a decade and raised and educated seven children. When he died, he owned his own home on the west side of Cleveland, Ohio. His was a Polish-American immigrant success story, largely due to his chameleon nature. Dziedziach, Dziedzikowski, Doski, Doskey. He assumed whatever shape the circumstances required of him, and from him my grandmother learned her dissembling ways. Harriet Hill was a force to be reckoned with: confident and well-spoken, she attracted admirers, well into her eighties. I’m forever grateful for the role model she provided; I am the continuation of her American success story. I honor her every day of my life. But how American was Hattie, really? Everyone, even her grandchildren, noticed that slight accent she couldn’t disguise, and how dark her olive-colored skin became if she went outside on hot, sunny days without a parasol.

Hattie Doskey, formerly Jadwiga Dziedzikowska, approximately 1916, aka “Grandma Hill”