I’m always a little surprised when I look at this blog’s statistics and see the number of hits. I don’t get thousands, but I have more than I expect. To those of you who are reading this, I thank you. I feel I owe it to you to tell a little bit about who I really am.

I’m a retired academic who always wanted to write fiction. Though the artistic part of my brain was badly fried by thirty-five years of teaching college composition, I managed to draft three novels and several short stories while fulfilling the requirements of a career that grew more demanding as the small liberal arts college I worked in drifted towards financial ruin. In the middle of COVID 2020, six months before my mother died, I retired. Revising my third novel pulled me through my grief. During my first couple drafts, I was worried I’d lost my ear. I credited that to having done very little reading for pleasure during my quest towards tenure at a small college in Buffalo. My workload at the Turkish university I worked at before that gave me enough personal time to savor reading fiction that wasn’t on one of my course syllabi. Umberto Eco, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Isabel Allende, Salman Rushdie, Orhan Pamuk, and Yasar Kemal became my companions. Since retiring, I’ve added Richard Powers, Olga Tokarczuk, Susannah Clark, Elif Shafak, Anthony Doerr, George Saunders, China Mieville, Louise Erdrich, Joy Williams, and Karen Thompson Walker to my list. Their books have helped me resuscitate the writerly soul I’d repressed beneath the armor I had to build to function in my job.

My adult life and my academic career began in the summer of 1985, when I was awarded a teaching assistantship and admission to Syracuse University’s Masters in Fiction Writing program. At the end of my second year, my story “Tonto, In The Trees” won the department’s Stephen Crane Award for short fiction. That same story appeared in the Nebraska Review and was named their Best Short Story of 1987. Syracuse was a turning point for me. My teaching assistantship gave me a career I enjoyed more than the medical secretarial work I was doing back in my hometown of Cleveland. So after finishing my M.A., I set off to become an academic who wrote fiction on the side. While some of my Syracuse colleagues went on to write their first best-selling novel, I completed a Ph.D. in Performance Studies at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and became a university professor. My dissertation, When The Voice Must Be The Body: Feminism and Radio Drama won the Tisch School of the Arts’ Cynthia Jean Bull Cohen Award for Academic Excellence in 1997. Chapters were published in Women in Performance and an issue of TDR that later became a book. An academic press offered to publish my dissertation if I was willing to edit. Go figure. I didn’t do it. I didn’t really want to write scholarly stuff. I wanted to write fiction. And I wanted to teach. You see, my family and friends were amazed when I finished a Masters degree. Many couldn’t believe I actually earned a Ph.D.. Especially me. I’d begun graduate school driven by the need to show myself what I was capable of. By the time I finished, I felt that if someone like me could accomplish what I had, others could, too. And I wanted to help them.

PAST REMEDIES

So, who is someone like me?

I was the second daughter in a family with three girls and two boys. We were your garden-variety dysfunctional family growing up in a brand new suburban development on the west side of Cleveland, Ohio. One step away from working class, my parents (and probably all of our neighbors, too) worked hard to pretend they’d attained the American dream. And yet, they maintained a working class attitude. Josh Robert Thompson describes the milieu of my childhood well during his appearance on the Honey Dew Podcast #117, “Cleveland has an interesting philosophy . . . don’t try too hard and don’t be proud of your work.” Furthermore, “growing up in a Catholic alcoholic family, you keep everything to yourself.” Listening to that podcast reminds me of my father’s alcohol cupboard. By the end of each month, the family would be eating bologna for dinner, but dad always had good gin. He taught me how to appreciate a good martini. Alcoholism was probably what attracted the different branches of my family tree – the Gorzynskis, the Dziedzikowskis, the Malloys, and the Thompsons – to each other. Yes, Thompsons. I’m related to Josh Robert Thompson. Second cousin, by adoption. I’ve never met him, though. But I knew his grandfather. Josh’s grandpa was my mom’s youngest uncle. On her mother’s side. My mother and grandmother boasted of him being an opera singer. On this podcast, Josh describes him as a gruff old World War II fighter pilot. Which he was, but my mom preferred to emphasize his more genteel side when he dropped by for a drink or two. What would Josh have to say about that? I don’t know. Estrangement from rough and tumble city relatives was integral to being a successful first generation suburbanite during the 1960’s and ’70’s.

Even if we had met, Josh wouldn’t remember me. I was the quietest kid in a family that kept to themselves. I was that Catholic school girl who showed up freshman year at the local public high school and never succeeded in fitting in. That girl who sat in the back of English class and didn’t talk. When teachers discovered I was a good writer and an astute reader, I was placed in Honor’s English and History, but I was never inducted into the National Honor Society. My mother called the school to complain, but they didn’t budge. I was socially clumsy. In retrospect, I suspect people thought there was something wrong with me. But there are degrees of “something wrong,” right? The biggest thing wrong about me was that socializing and talking didn’t come easily. But writing did.

I experienced my undergraduate English degree at Cleveland State University as a first-generation college student. I had no role models. Sure, my father had earned a college degree on the GI Bill, but he was rarely home. Luckily, I had compassionate teachers who made it a point to tell me I was a very good writer. One recommended me to work in the tutorial center, so in 1978 (the same year my father died) I began learning how to talk to strangers about something I knew a lot about: English composition. I discovered that I enjoyed the reciprocality of teaching language to someone from another country. We both grew from knowing each other. During my Master’s, I took TESOL methodology courses alongside my writing and literature courses but never gained a certification. I continued tutoring and teaching international students at N. Y. U. and the Cooper Union. By the end of my Ph.D., I’d begun developing ideas about how to use performance theory in the ESL classroom. However, I felt that, to be an effective language teacher, I needed to learn what it felt like to be a foreigner in a land whose language I didn’t speak. My first full-time teaching position (1999-2003) was in the Department of American Culture and Literature at Baskent University in Ankara, Turkey. There, I taught expository and creative writing, performance theory and world fiction and drama. I helped build a composition curriculum and a Master’s program. In my spare time, I wrote a novel – an updated Othello set on modern Turkish Cyprus called Past Remedies. That unpublished novel received an Honorable Mention in the 2004 Peacewriting Contest.

My Turkish colleagues and neighbors were kind to me before, during and after 9/11, but when the United States invaded Iraq, anti-American sentiment grew. I encountered it in grocery stores and on busses. My stepfather died in March 2003, leaving my mother alone in a big house outside Cleveland, and I decided it was time to go home. A former colleague helped me secure a one-year position at Alcorn State University in Mississippi, where I was able to do an in-country search for a tenure track job as close to Cleveland as possible.

YOU LOOK GREAT TOGETHER

Medaille College in Buffalo, New York was full of first-generation college students who reminded me a lot of myself. Among the Medaille faculty, I found many other overachievers from working class families. We all did our best to give our largely urban student population a leg up. I took it upon myself to teach my American students global literacy. During my first six years at Medaille, former Turkish colleagues and I worked on building cross-cultural writing wikis where students from America and Turkey collaborated on assignments. At conferences I attended in America and abroad, I was one of few discussing digitally enhanced collaborative writing assignments. My pedagogical innovations waned as my administrative duties increased. During my years at Medaille, I held the following titles: Humanities Chair, English Chair, and Humanities Division Head. I helped build Medaille’s International Program. When I retired, I managed the Write Thing Reading Program as part of my duties as English Program Director. I was also building remedial reading and writing programs. I spent hours every night grading student papers.

Rust belt cities like Buffalo and Cleveland are full of small colleges like Medaille. Today, many of these colleges are facing closure, if they haven’t closed already. Many have stories similar to Medaille’s case. “The Sisters of St. Joseph of Medaille opened the Institute of the Sisters of Saint Joseph in 1875” on the land that later became Medaille’s campus. The school became known as Mount Saint Joseph Teachers’ College, and it started offering degrees 1937 (“Medaille University” Wikipedia). In the 1960’s and 1970’s, families looking for a small college where their Baby Boom and Gen X children could get personal attention were happy to send them to places like Medaille. As student numbers dwindled at the turn of the twenty-first century, those schools became more specialized in order to survive. Some didn’t. Medaille closed in 2022. When I joined its faculty in 2004, the signature program was Veterinary Technology. Medaille’s Vet Tech students inspired me to draft a mystery novel, You Look Great Together. The sleuths are triplet sisters: one a vet, another a vet tech, the third, a doggy day care owner. The mystery begins when a prize-winning German Shepard is abandoned at day care and the sisters find themselves solving a mysterious disappearance when they go looking for his owner. It was a fun book to write, but as with Past Remedies, it was set aside because of the increasing demands of my job. Reading Richard Osman’s Thursday Night Murder Club has me itching to revise You Look Great Together and begin a sequel, where the pet that initiates the mystery is a Maine Coon.

My annual performance review at Medaille required that I account for scholarship, service, mentorship and teaching, with the last three being the most important. This emphasis on student teaching and community building was why I stayed at Medaille. Our evolving student population demanded creativity and risk taking. One day one of my non-traditional female students approached me after a lecture on The Fool in King Lear that featured my tarot cards. She wanted to begin a new club – a paranormal society – and she needed a faculty sponsor. I seemed like someone who would do it. She was right. I was the Medaille College Paranormal Society’s faculty advisor for several years before handing it off to a more psychic colleague. By the time Medaille closed its doors for good, it was the most popular club on campus.

THE DOUBLE-SOULED SON

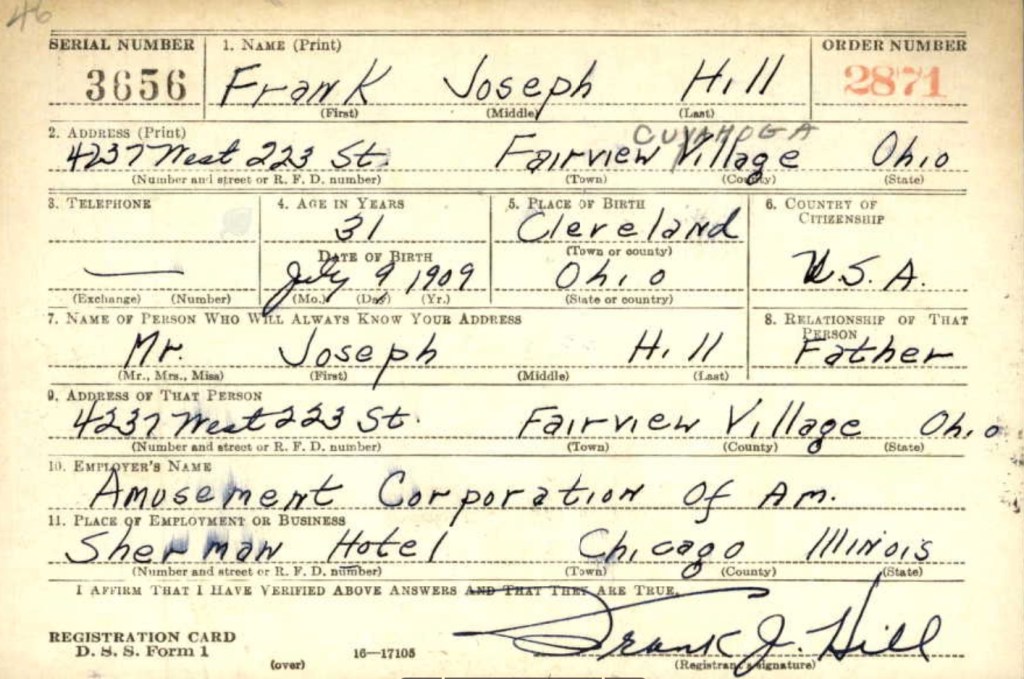

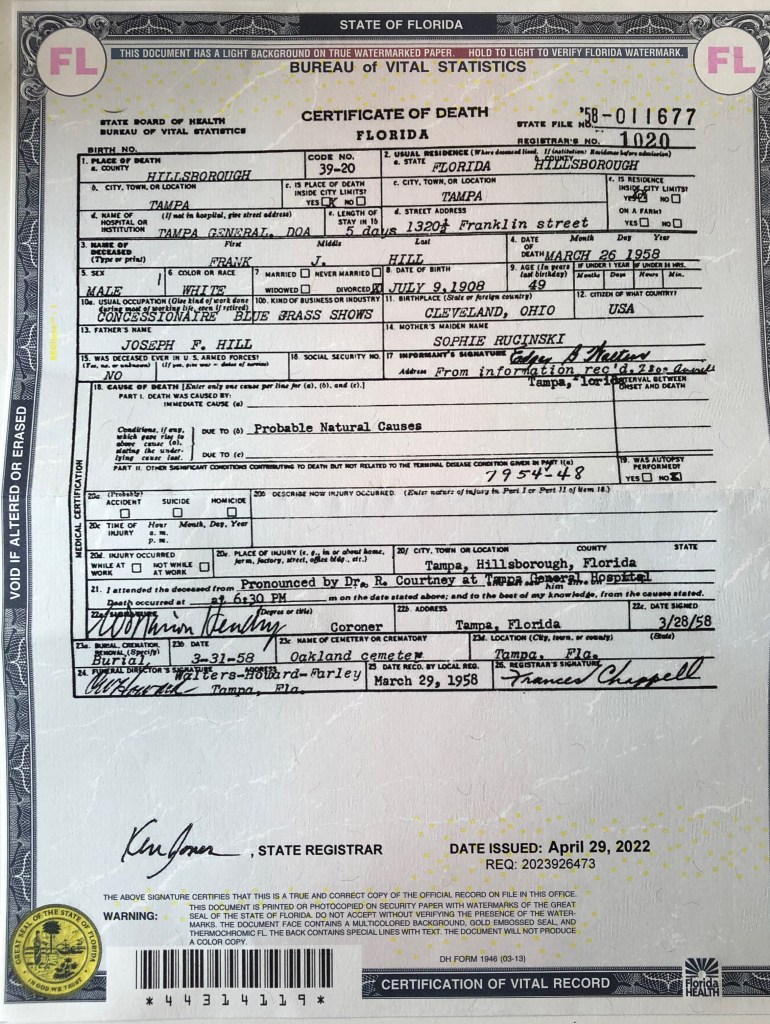

Two years before my 2020 retirement, I took my first and only year-long sabbatical. That was when I drafted The Double-Souled Son, the novel I’m marketing now. Based on research into my father’s mysterious family, it’s a paranormal-psychological literary family saga of a late nineteenth century misfit couple’s migration from Poland to America. Taking its cue from Mohsin Hamid’s line “we’re all migrants in time,” The Double-Souled Son imagines the psychological traumas these ancestors suffered before, during, and after their migration. The characters were conceived to embody the multiple personalities Poles had to negotiate during the nineteenth century. One was religious: “Scholars who investigated Slavic folk beliefs in the nineteenth century were astounded by the extent to which the peasants, while practising [sic] Orthodox Christianity, were still connected to their pagan inheritance. The phenomenon became known as dvoeverie, or ‘dual faith.'” (Myth and Mankind: Forests of the Vampire: Slavic Myth). This was especially true in rural Poland, where the peasants proudly maintained their Polish language and traditions while also dealing with Prussian, Russian, or Hungarian occupiers. When they arrived to in America in 1881, they were already psychologically damaged. Life in a mining company town in Pennsylvania, Buffalo’s stockyards, and Cleveland’s industrial Polonia only compounded it.

Medaille’s second largest program was Psychology. Student research papers about trauma sparked my own interest, as a family historian, in epigenetic trauma. I theorized that unresolved trauma that gets passed on from one generation to the next produces dissociated personalities. Around the time I retired, I began untangling my own dissociations, tracing them to the stages in my life that induced them, and I found some predate my memory. They may have been sparked by an initial trauma that occurred generations ago. Back then, no one talked about “dissociative identity disorder” or “multiple personality disorder.” Pre-modern cultures made sense of these conditions with superstition and myth. In rural Poland, people believed that someone with contradictory personalities had two souls. One of those souls was an average soul, the other supernatural: a strzyga. Graves of the suspected double-souled provide evidence that this belief continued into the twentieth century. My 2019 visit to Krakow’s Rynek Underground Museum included a display of corpses decapitated, secured, and buried face down.

Seem extreme? Well, the strzyga is a cousin to the vampire, capable of inhabiting cast-off bodies and returning to life. My interpretation of being double-souled emphasizes the human over the demon. CulturePL’s video “The Strzygon Soul And How To Deal With Him” offers a humorous depiction of this affliction. In this video, the body, possessed by its supernatural soul, climbs out of his grave, returns to his wife and has more children. He’s only half-bad, after all. And even when he’s bad, he has a good sense of humor. In the book, I’ve imagined a family known to produce double-souled children. The entire village is on high alert when the protagonist is born. The signs are clear from the infant’s first holler: he’s born with teeth and has a strange birth marks. And here’s the hitch: his curse won’t go away, even when he and his family migrates. In a place like America, the double-souled son may still be half demon on the inside, but to his immediate community, he’s crazy.

Therein lies the inspiration for The Double-Souled Son. This novel begins in Prussian-occupied Poland in 1861 and ends in Buffalo, New York, in 1901, where every Polish immigrant’s reputation was further tarnished by a young man named Leon Czolgosz who he assassinated President McKinley. This is the first of two books on how “starting in the late 19th century, traditional sources of identity such as class, religion, and community slowly began to be replaced with an emphasis on personal growth and happiness,” (“A Family Therapist Looks to Historians for Insight on the Changing Forms of Family Estrangement“). There’s a sequel in progress called American Limbo, in which the strzygon soul reincarnates during the 1920’s in Cleveland’s Polonia. Ten years after his mother’s early death, his father remarries a younger woman who insists they assimilate when she has her own child. The newly minted American family moves to the suburbs, and the outcast strzygon becomes a carnival worker, and his migrations continue.

Though it occasionally goes off theme, Baba Yaga’s Journal is primarily a collection of sources from my research. It recaptures stories about the Poland my ancestors left behind, including what happened in my ancestors’ home villages during World Wars I and II, and beyond. These were the stories my father’s family opted not to tell me. My grandmother said she did it to protect me. And, dare I say, to make me pure American. And therein lies the heart of my proposal: that researching family history and studying the socio-political conditions that caused a family to migrate can increase anyone’s awareness of how we are all historically constructed global citizens. Indeed, we are all migrants in a complex web of time, and our children will continue to be so, into the future.