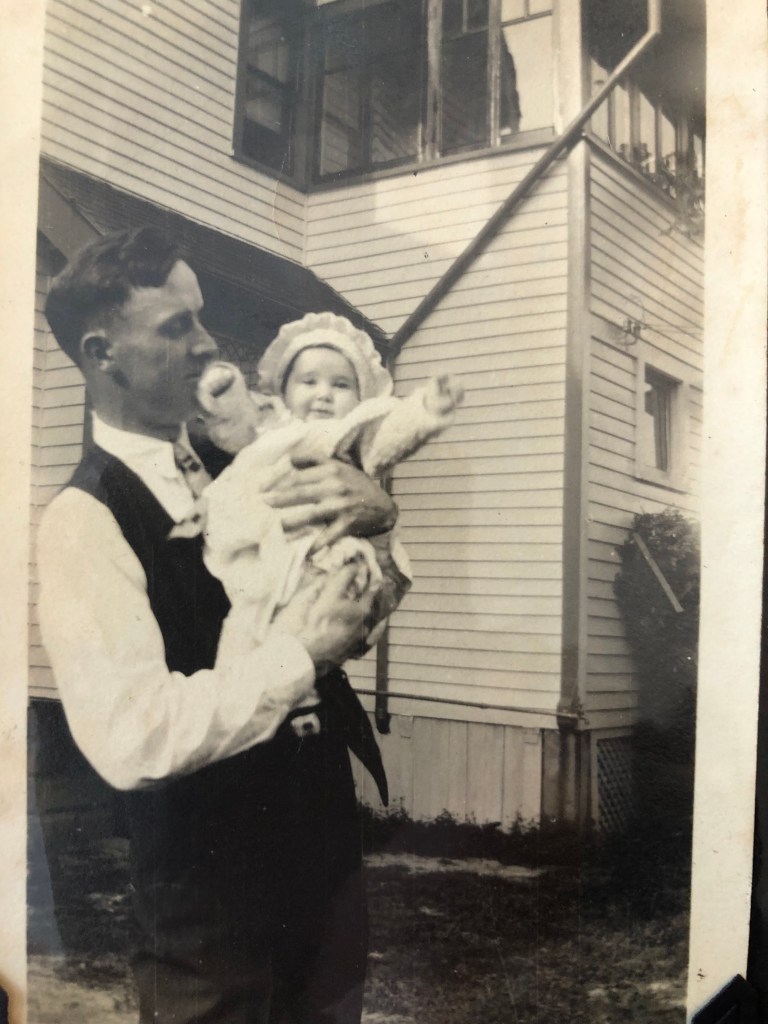

This was my favorite family photo when I was a girl. It was taken June 10, 1950, the day my parents, Katie and Myron, began the story of the family that produced me.

I’m not a child anymore. I still like the photo, but for different reasons. At sixty-six, I’m retired from two careers: one in higher education, the other as my mother’s confidante. Second eldest of Katie and Myron’s five children, I was the child who didn’t talk much. The one who hid in her bedroom most of the time. The one who sat in the back of classrooms; the one who was the last to be picked on softball teams. In grade school, high school, and college I had trouble putting thoughts into speech. So, I spent a lot of time listening. And smiling. Talking to me was probably a bit like talking to yourself. That, I believe, is why Mom told me the things she otherwise kept to herself. She needed to say them out loud, and I provided a sounding board. Even after my language aptitude began manifesting, she continued confiding in me. My reading and writing skills matured quickly. I liked writing stories; everything around me was fair game. Yet she kept telling me things she didn’t tell anyone else. Did she want me to keep these as secrets? Yes, I concluded. So, for forty years or so I didn’t write much, and when I wrote a story, it wasn’t one of those burning inside of me. I published a few, was short listed for a few awards. The stories were good, even though I wasn’t sure what they were about, and a reader could tell that.

Katie died Christmas Morning, 2020. I retired six months later. My mourning lasted four years, give or take a month or two. Writing a novel helped me through it. I revised and edited in rooms decorated with family photos, both my husband’s and mine.

As I streamlined my narrative and solidified characters, I began seeing stories everywhere. When I meditated on my own family photos, I felt Katie standing behind me. She spoke to me from the beyond. Remember what I told you about that day? Remember what happens next? Oh, yes, I remember. What happened next was happy for a little while, before it turned tragic – imagine a 1970’s Cleveland suburban Othello meets Death of a Salesman – it left my siblings and I scarred. Even today, emotional roadblocks limit our ability to reach out to each other. Why? The answer might lie in this wedding photo.

So, look again. Katie’s wearing a rented dress. She always regretted not buying it. And the flower girl’s dress was stolen from her father’s car later that day. The wedding party spent plenty of time in cars, driving back and forth between two receptions. Myron’s mother refused to celebrate with my mother’s kin. You see, Katie was working class Irish. Her dad was a Cleveland cop who’d served for years on the streets before being promoted to City Court bailiff.

Is that wedding party smiling? Or simply posing?

From the look on her face, I can tell Katie already knew how to maintain her composure while screaming inside. That was a skill she passed on to me. My family rarely shared what we were really feeling. Anyone who did was deemed hysterical, or out of line.

The bridesmaids are Katie’s sisters, my aunts Rosie and Mary Lou. Their smiles are sincere; they’re happy for their big sister. They hope they, too, will snag a handsome, wealthy man. Though they’d never seen it (and they never would), they’d heard about Myron’s parent’s sweet little house in Fairview. Its big garden with an apple and a pear tree. Roses everywhere! And two automobiles, which made Katie’s brother Jim jealous. Jim’s the man on the left. He’s not overjoyed. He’s been suspicious of Myron all along. But Jim loves his big sister and wants to support her, so he’s rising to the ceremony.

I never met the best man. The day I overheard my mother talking about his death I learned the word suicide.

These details may suggest a misalliance, but actually, Katie and Myron were meant for each other. They shared the same nebulous American Dream, inspired by movies, radio, and early television. They each endured a Depression era childhood. Both lost friends in the second world war. Myron served as an Army military policeman in postwar Italy and France. Everywhere he went, he was greeted as an ambassador from the United States, the defender of democracy. When this photo was taken, he was in college, thanks to the GI Bill. Katie had a secretarial job. They both were good Catholics who agreed they were ready to embark on crafting a new American family identity, here in this land of the brave and the home of the free.

As with most new identities, theirs required a change of location. The apartment they moved into after the honeymoon was chosen for being equidistant between parents. For Katie, her family was a bus ride away. When they finally bought their Dream House in the suburbs, the Myron Hills were within walking distance of his mother. Katie, on the other hand, had to learn to drive. Her parents still lived in a working-class neighborhood on Cleveland’s West Side. She was the first in her family to move to the suburbs.

Myron was only three when his family migrated from the city, so he didn’t remember living anywhere else. I grew up believing the Hills were one of Fairview’s founding families. Grandma Hill worked hard to perpetuate that myth. Grandpa Hill might have told us otherwise, but he died the year I was born. The hints he left behind were tantalizing. That old punching bag in Grandma’s basement? His. He used to be a boxer. That funny shed-like extension on the garage? It once housed Grandpa’s chickens and roosters. He was a cock fighter. Those heavy scissors were his: he used them to cut wallpaper. That hammer – he got it from his father. The men in his family were carpenters. During the depression, Joe and Harriett signed a lease for the house Myron grew up in. What Grandma called her Dream House was unfinished when they bought it. Though it was the depression, they paid it off in six months, while Joe completed the interior work. It provided the setting for Myron’s growing up.

“We never know what we don’t know” became my mother’s motto as she grew older. In June 1950, she hadn’t realized its irony. In the photo, her eyes betray her anxiety. She was determined to be a good wife, to keep a good home, to bear healthy children and raise them in a loving home. When it came to being an obedient daughter-in-law, she was already at a disadvantage. Harriet Hill never hid her disappointment about her son’s choice. When she first realized their relationship was growing serious, Harriet told Katie to break up with Myron. Katie obeyed. She stayed away until her best friend Jeannie (who was going steady with Myron’s bestie Richard) told Myron, who begged Katie to return to him. Katie obeyed. She was a good girl. That’s what everyone said about her. What few understood was how smart she was. Family and friends realized that after Myron died. But at twenty-two, Katie kept her “smarts” under wraps, lest it spoil her complexion or extinguish that glint in her eye.

Oh, what we don’t know.

Now recognized as the Greatest Generation, my parents and their contemporaries were heralded for the accomplishments they gained despite poverty, hunger, epidemic, and war. As children or grandchildren of immigrants, many members of that generation still knew the stories of their ancestors’ journey from the Old Country. That only hardened their resolve to build a better America for their children. Sadly, many of those stories didn’t get passed down. Those that featured a lot of suffering were most likely to remain untold. “What you don’t know won’t hurt you.” That’s what my father and his mother used to say when I asked about family history. “Let’s just say it was awful. Be grateful you’ll never have troubles like that.” And thus, they kept my siblings and I locked in a suburban bubble where we were led to believe everything had its place and every ending was happy. Thanks to them, I’ve lived a lucky life. My successes, which surpassed my childhood dreams, were fueled by the naivety that comes with not knowing what my immigrant ancestors forfeited for me. Like much of my generation, I lived flamboyantly, performing my parents’ American Dreams admirably. With only a dim idea where my ancestors came from, I had no idea when and how they migrated. When I’d ask my father, he’d laugh and say “my parents found me under a rock.”

Nations that keep their identity intact can survive history’s violent cycles. The same can be said for families. I learned that lesson from my mother’s Irish kin. Some of my warmest childhood memories occurred on our two-week summer vacations to Pennsylvania’s Endless Mountains. Today a mecca for hunters and nature lovers, I knew this Appalachian subregion as the location of the dairy farm where my Grandpa Malloy grew up. The cows were sold when I was four years old, but Grandpa’s brother Rod and sister Marge maintained the remaining three hundred acres by renting them out for other farmers to harvest. The fields were neatly plowed; the barn and the outbuildings were all functional, and everything still smelled like cow manure. The farm’s hilltop position gave us a picture-perfect view of the nearby Roman Catholic Church, St. Anthony’s of Padua, erected in 1860 by the Irish potato famine migrants buried in the cemetery around it. “You’re related to all of them,” Marge would say, when we accompanied her on our requisite annual walk through the graveyard. My siblings and I were otherwise free to spend our daylight hours exploring the fields, rowing in the pond, jumping out of the hayloft, or shooting at targets. At night we’d sit on the front porch with Rod and Marge, drinking root beer floats and listening to stories. Marge knew all the family gossip, and she told it. Who came from Ireland first, and who went back home. Who married who, who was an orphan. Which uncle went to prison; which cousin became a famous meteorologist. While Marge talked about people, Rod told us about the land. He loved every inch of their century farm, both tillable and forested. He had no desire to leave it. Only once, in his twenties, did he leave the farm, hopping a train to go to a Brooklyn Dodger’s game. After his team lost, he hopped another train back home. He realized he had to stay on the land that nurtured him. Its landscapes reminded him who he was. He knew its legends. Jimmy Hoffa was probably buried on the abandoned Murray farm. Mountain lions lived in the forest. Bear, too. Rod himself spotted a UFO over Tyler Mountain. My mom egged him on, talking about the time she got attacked by a pig. In this reminiscing, family history and local legend merged. My siblings and I felt like we were part of it.

And yet we weren’t. Our father was awkward at The Farm. Only once did he admit his father’s parents had lived nearby, in Nanticoke. Otherwise, he didn’t speak much.

What did he hold inside? Was he trying hard not to blurt out the thing Katie didn’t know back in June 1950? The thing she must never know? That Myron John Hill was a pseudonym, an Americanization of his paternal and maternal grandfather’s names, combined. “Myron,” when spoken a certain way, sounds like the Polish male name Marian. As in Marian Gorzynski, the grandfather whose first American job was in Nanticoke’s mines. “John” salutes Jan Dziedziach, aka Dziedziekowski, aka Doski, aka Doskey. Hill is a translation of the góra in Górzyński. This type of translation happened a lot, I’ve been told, when the children of Polish peasants who immigrated to the United States in the late nineteenth century decided to assimilate. After the son of a Polish immigrant killed President McKinley in 1901, the pressure to melt into mainstream white America increased. Especially in Cleveland, where the assassin Leon Czolgosz’s family lived. Even after the assassination, Pavel Czolgosz and his other sons didn’t change their names. Didn’t move away. The Czolgosz family’s migration story ended in Cleveland’s Polonia. They intended to die there, and they did.

Myron died after a series of heart attacks late in 1978; a stroke killed his mother in 1984. Katie died in 2020, of Lewy Body Dementia. By 2017, I knew the truth about my father’s name, thanks to Ancestry.com, Family Search, and the Polish Genealogical Society of America. In her final years, Katie grew brutally honest. She understood things about herself and Myron that she didn’t know when she married him, and she was angry. (“I don’t know who I married! Whose children did I carry?” she said to me once, three years before she died.) When I presented her with the story of our real surname, I asked if she would have married Myron Hill had he been named Marian Gorzynski.

“I wouldn’t have looked twice at him,” she replied. “My folks didn’t have anything to do with Polacks.”