Of all the inheritances one might lose, family histories are the most valuable. Money, jewelry, and furniture take second place to the stories our ancestors hoped would get passed down from one generation to the next.

*

My mom’s Lewy Body Dementia was in full blossom when we moved her to memory care in 2019, right before COVID cast us all into isolation. The facility was only blocks away from the home Mom and her second husband bought in 1982. Every inch of that house and garden was designed and decorated by her. Only a few of her precious items moved with her to the room where she died. Everything else was up for grabs.

Like many mothers, mine had a highly refined sixth sense. She could read your mind. She saw through her children’s deceptions so easily. At an early age, I decided my best strategy was to always tell the truth. It wasn’t surprising, then, that Mom knew the day her house sold, though no one told her. She was inconsolable on the day its contents were “secretly” liquidated. Each of her five children collected what we could pack into our cars before all the rest was taken away in a truck to parts unknown. Mom’s beloved octagon table, her selection of paintings and mirrors, her quilting fabrics, her piano, her organ, and her porch swing became anonymous finds in some second-hand store. That’s how family histories are lost, by the way. The keeper of the history dies or the last survivor of a generation gets sick during plague. Or there’s a fire. Or a war. Often, the next generation chooses to disengage from their immediate family. Memorabilia gets cast aside, its stories forgotten.

*

The current popularity of Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Finding Your Roots signals a collective nostalgia for boxes left behind in some attic, somewhere, sometime during the 1990’s. Many of my fellow family historians have become pretty adept at fleshing out complex family histories. Some of us can trace American identity to the first wave of Western Europeans who broached this nation’s shores. I can do that on my maternal grandmother’s side, where I qualify to be a Daughter of the American Revolution six times over . . . and counting. On my father’s side, I trace my American identity to a migrant worker and his wife. Members of the Polish Peasant Diaspora, they were not welcome in America. We know the derogatory terms they encountered. Sometime during the 1970’s, mainstream America agreed not to use them anymore. DNA tells me my father was 100% Polish. His parents wouldn’t admit this while they were alive. I don’t blame them. They wanted to rise above the embarrassing stereotype attached to being Polish and pave the way for my generation to enjoy the American Dream. So our grandparents assimilated. Changed names. Changed locations. Some changed locations so many times, it’s as if they never stopped migrating. I’ve found death certificates for my relatives in cities all over the United States. Addresses confirm they never left the working class. They lived in company towns, industrial workers’ quarters, and densely populated ethnic urban neighborhoods. Many of them died young. Renal failure, cirrhosis, tuberculosis, and diabetes are among the most common causes of death.

Rebuilding a family tree becomes very difficult when ancestors relocated often, and were prone to changing their name. But not impossible. In my case, DNA results only confirmed suspicions. DNA doesn’t get you very far if you don’t have the proper surname. I have countless DNA matches on my father’s side that are only that: DNA matches. Their names are like Hill: Smith, Martin, Jessica, Rose. A generation or two back, an ancestor assumed an alias and began creating legal documents to support their revision of the family’s past. Little did they know that their grandchildren would have access to FamilySearch and Ancestry.com. There’s always a crack in the wall of documents created by ambitious migrants trying to rewrite their family’s history. For me, it was a pair of wedding documents.

*

My mother told me when I was eleven that my name wasn’t really Hill. She had written down a name she found in an obituary, but it was wrong. In my thirties, I became very tired of the blandness of “Hill.” I decided to find my true surname. I knew my father’s parents changed it. So, I wrote a letter to the pastor at the church where my grandmother told me she and grandpa wed, requesting a copy of his marriage registry on October 10, 1917. The pastor wrote back. He sent me this:

When they married, my grandparents were using variations on their Polish names. Twenty years later, I discovered on Family Search that”Doski” was first used by my grandmother’s family on the 1900 census. “Gozinski” is a misspelling. The proper spelling of my grandparents childhood surnames appeared on another wedding registry. The two witnesses to my grandparents’ nuptials were Grandpa’s sister Helen and Grandma’s brother, Clarence (aka Clemens) A few years later, Helen and Clem married.

*

On the day I walked into my mother’s vacant house to collect the things I wanted, I felt a bit like a stranger. She raised Mary Louise Hill (aka Mary Lou aka Louie aka Babe) in a void. I took after my father. Not knowing my father’s family, she didn’t recognize their traits in me. She didn’t know how to guide me.

I took mom’s sewing machine and a few pretty ribbons from collection. I took an antique mirror and some ceramic bowls from my maternal grandfather’s ancestral farm in Pennsylvania. And I took all of the old photo albums and memorabilia. Boxes of them, from all sides of the family. On visits home, I spent time sorting them out. I knew what was in those boxes, but I left them in Mom’s basement so other family members could have access to them. In the end, no one wanted them. I took them.

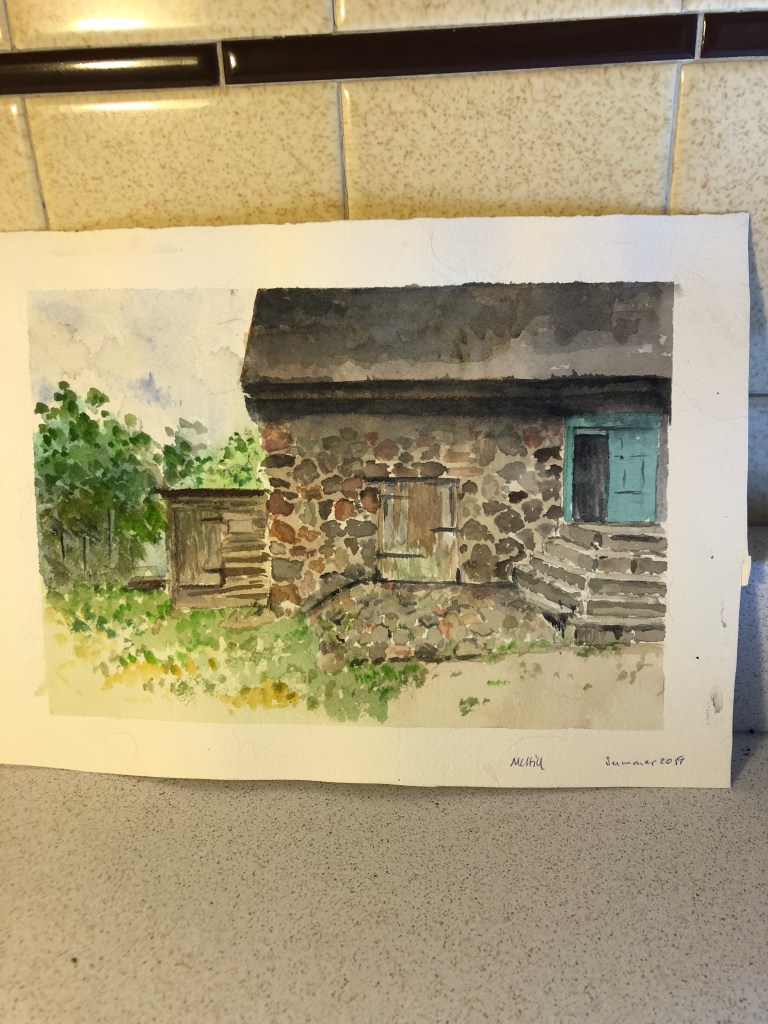

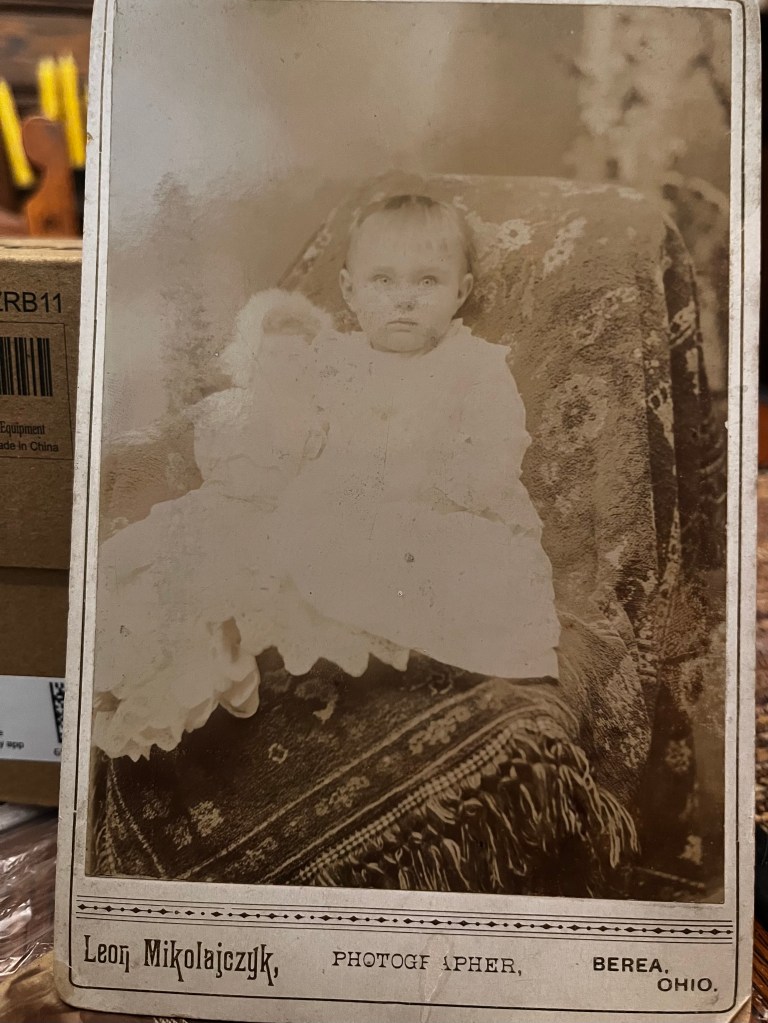

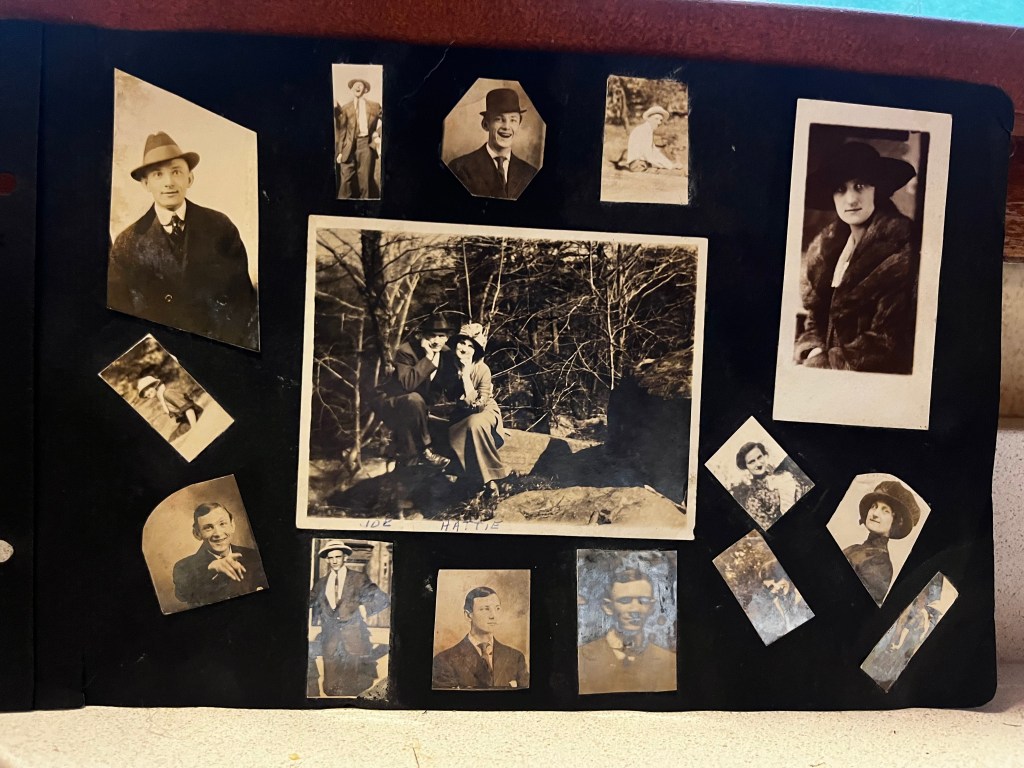

My mother took meticulous care of her own family’s photos, and they’re all marked well. (The display in the first photo above are hers.) Not so with my father’s family. It’s not that they didn’t take photos. Photography was one of Grandma Hill’s hobbies. She had multiple cameras, and she carried one of them almost everywhere she went. She took great care to organize her photos into albums. The problem is, she didn’t label anything. These were albums created for her own enjoyment.

Over time, I’ve learned to identify many faces in my father’s family. The anchor photo is always my grandmother. Hattie. She had very distinctive facial features, so it wasn’t difficult to identify younger versions of her.

That nose and those eyes helped me identify photos from every stage in her life.

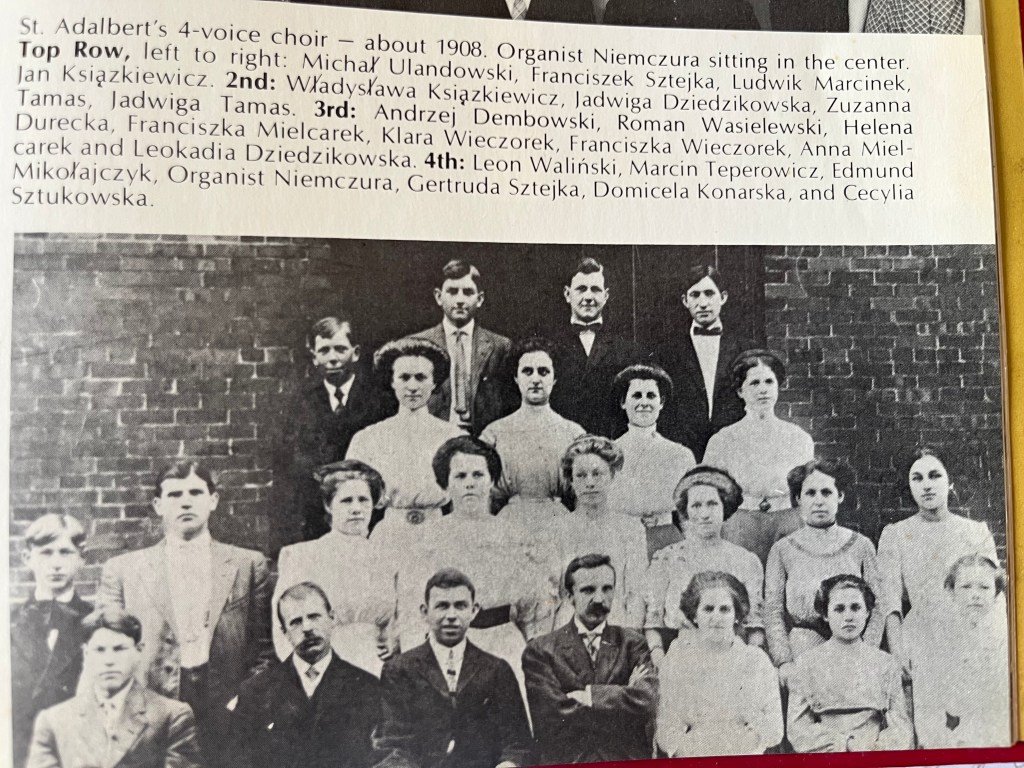

According to censuses and other public records for Berea, Ohio at the turn of the twentieth century, the woman I knew as Hattie Hill was called Jadwiga Dziedziekowski as a girl. A photo of her church’s choir in the centennial anniversary book confirmed that name and its spelling. This photo also informed me that my Aunt Charlotte was originally named Leokadia.

*

Migration – whether it’s from city to suburb, state to state, or country to country – is a sure fire way to become estranged from one’s past. Many families in Poland know they had relatives who left during their nineteenth century Partition. They have no idea where they ended up. I wrote a blog entry about the Dziedziekowskis several months ago which caught the attention of a Polish family historian with a mother who wanted to know what happened to her disappeared ancestors. The researcher recognized my tale as that of a long-lost relative. After exchanging photos, we decided we were distant cousins. When she finally admitted her father came from Poland, my grandmother told me I was the great-grandchild of Polish aristocrats. My new cousin informed me that was a lie: great-grandpa was from a hard working Christian peasant family called Dziedziach. His story had been passed down in her mother’s family: he and his brother Stanislaus had disappeared after their father died. When their mother remarried, they took off, never to be heard from again.

*

Though I lived in Buffalo and Mom lived in Cleveland, I visited her as often as I could. We were close. She often confided in me. One day, while she was still living at home, she asked me to get a particular sweater from one of the drawers. She was in the early stages of her dementia already, and nothing was where she thought it was. While looking for her sweater, I found this:

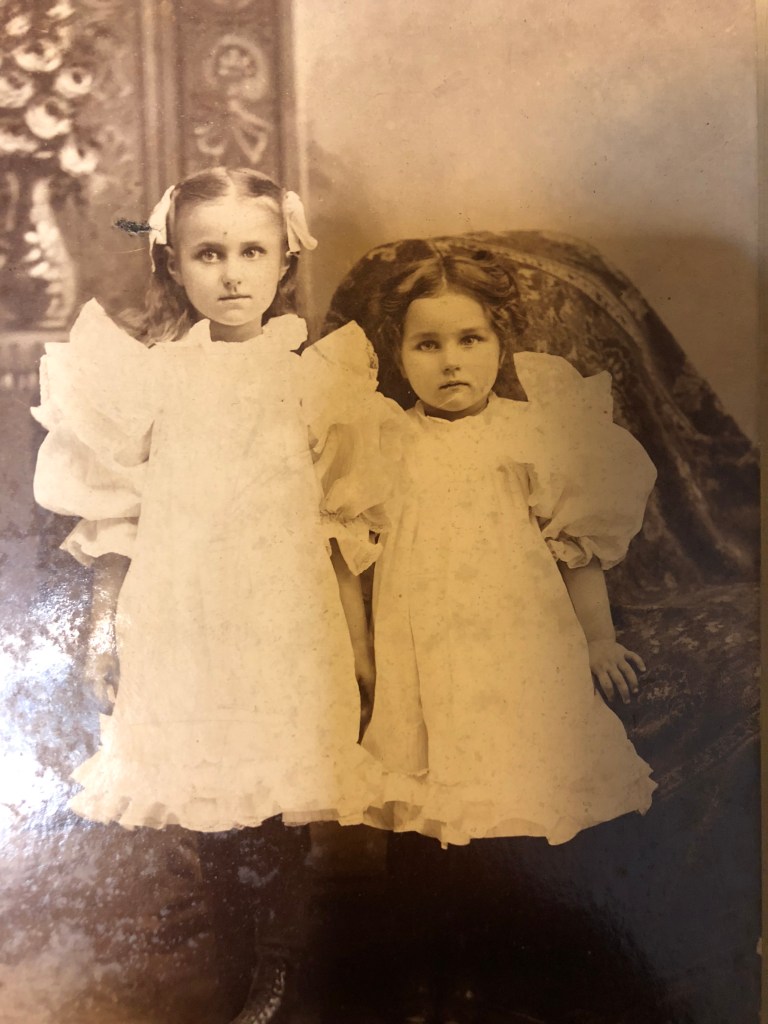

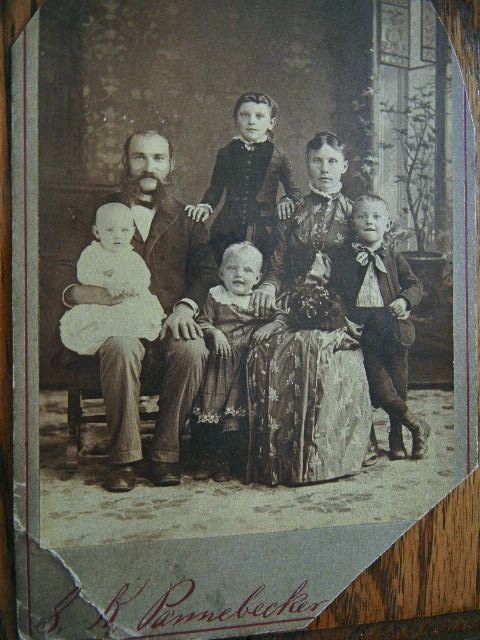

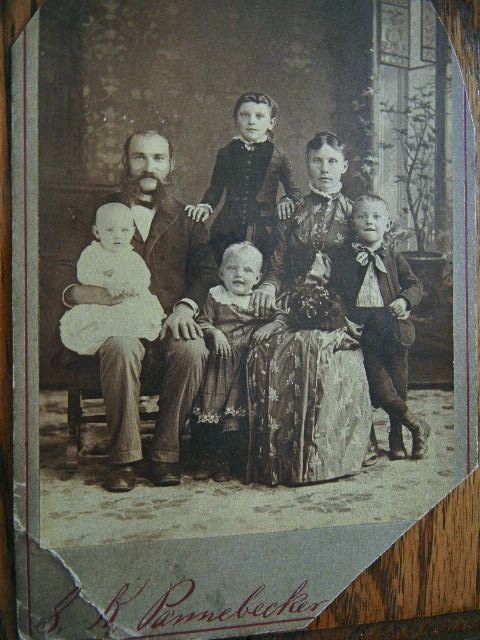

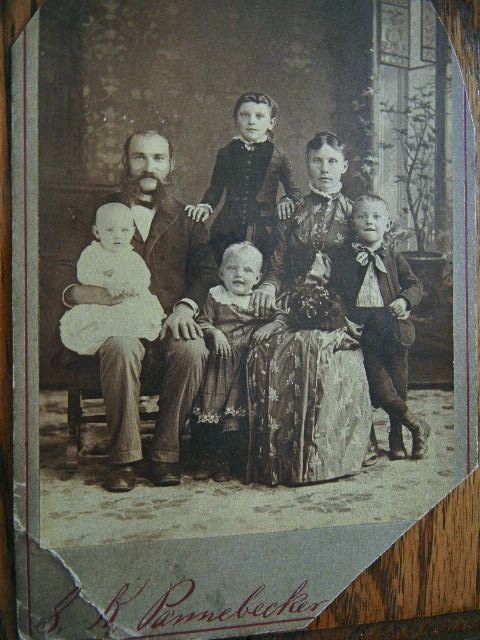

My mother was upset when I handed her both the sweater and this photo. She demanded I return the photo to where I found it. She knew it was the branch of the family I was most obsessed with. She’d written the name “Hill” on the back. And I could easily recognize my young grandfather. You see, even though I never met the man, I knew from photos that my grandfather had pretty distinctive features, too. Here’s a page from Grandma’s album that features she and Joe when they were courting. Grandma’s sweetheart is none other than the little boy leaning against his mother’s knee in the family photo.

The Górzyński family photo tickles me. Grandpa Joe and his family laugh with me across time. My great-grandfather Marian – Oh my! I can imagine him winking. I estimate his photo was taken between 1895 and 1901, when no one smiled for photos. Anyone who did was considered a little inappropriate. On showing this to my seven-year-old nephew, he labeled it”the silly family.”

The silly family. The ancestors no one wanted to talk about. Were they silly? Were they embarrassing? Were they in the mafia? Or did they simply refuse to assimilate? My grandfather’s parents were migrants for a long time. They moved several times before they owned their own home. They always lived in the Polish enclave. Creating America’s Polonia was a process: villages reunited in working class areas near America’s mines, factories, and stockyards. At the turn of the twentieth century in Cleveland, Warszawa, the Polish neighborhood my family settled in, “was, in essence, a Polish town situated in the corporate limits of Cleveland” (Polish Americans and Their Communities in Cleveland, by John J. Grabowski, Judith Zielinski-Zak, Alice Boberg, and Ralph Wroblewski.) That community flourished as long as it could remain isolated. President McKinley’s assassination was the first of several events that forced the assimilation of Polonia into the urban Cleveland landscape.

Great-Grandpa Marian (often called Frank) died in 1914. Franciszka stayed in the Warszawa house her husband built for her until she died. That house – a double with a livable attic – is still standing. In 1920, the house was functioning as my great-grandparents had intended: Great-Grandma lived there with Walter and his family, and Joe and his family, plus Helen and John, both still single. After Walter died and his wife and daughters moved out, Helen married Clem, and their family moved in. My grandparents moved out when my father was born. Helen and Clem stayed on with great-grandma for a few more years before finding their own suburban home. During the 1930’s Grandchildren moved into the family home, but they didn’t last long. By 1939, when Franciszka died, she had tenants. The final census she appears on – 1930 – lists her as illiterate, her language, Polish. At the time of her death, her eldest living son – and possibly the child who was in line to inherit the house – was my grandfather. By then, Joe and Hattie lived in the suburbs. It appears Joe washed his hands of the family situation completely. Franciszka’s death certificate and the documents marking the sale of the house were signed by Grandpa’s youngest brother Eddie, who still lived nearby. It’s amazing this photo remained in our possession. Although mom kept us hidden from us, I credit her with keeping it. She valued family history, even when it was a little embarrassing.

Embarrassing by whose standards, though? My research suggests otherwise. To their family back in Poland, they were a success story. Until they lost touch. This photo was taken to send to someone. Chances are, copies of it went to Poland, where everyone knew the beginning of this family’s story.

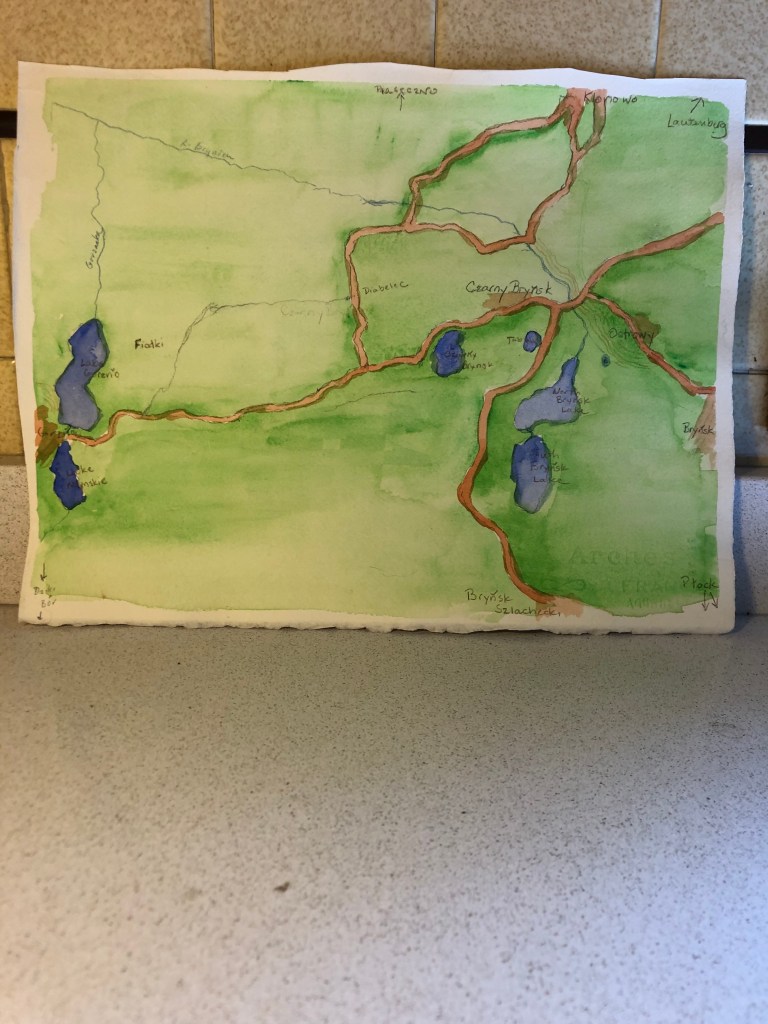

Marian Gorzynski was orphaned at age three when his mother died and his father moved away and remarried. When Marian married, he lived in Czarny Bryńsk, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivoideship, Poland and had a respected trade: he was a wheelwright. Franciszka Golembiewska was the eldest daughter of an esteemed family in nearby Bryńsk-Ostrowy (shown on maps as Ostrowy), Warmian-Mazurian Voivoideship, Poland. These villages were among several satellite settlements of the nearby settlement called Bryńsk. (Marian’s father was born there.) Franciszka’s father Thomas bequeathed a slice of his land to his community, where he erected a wooden cross for travelers to pray before leaving town. When that cross was destroyed, the village erected another. I’m very grateful to a contact I made through the Facebook page Orędowdnik Wielkiego Lasu who has shared this story as well as photos of the current cross marking the former Gołembiewski land.

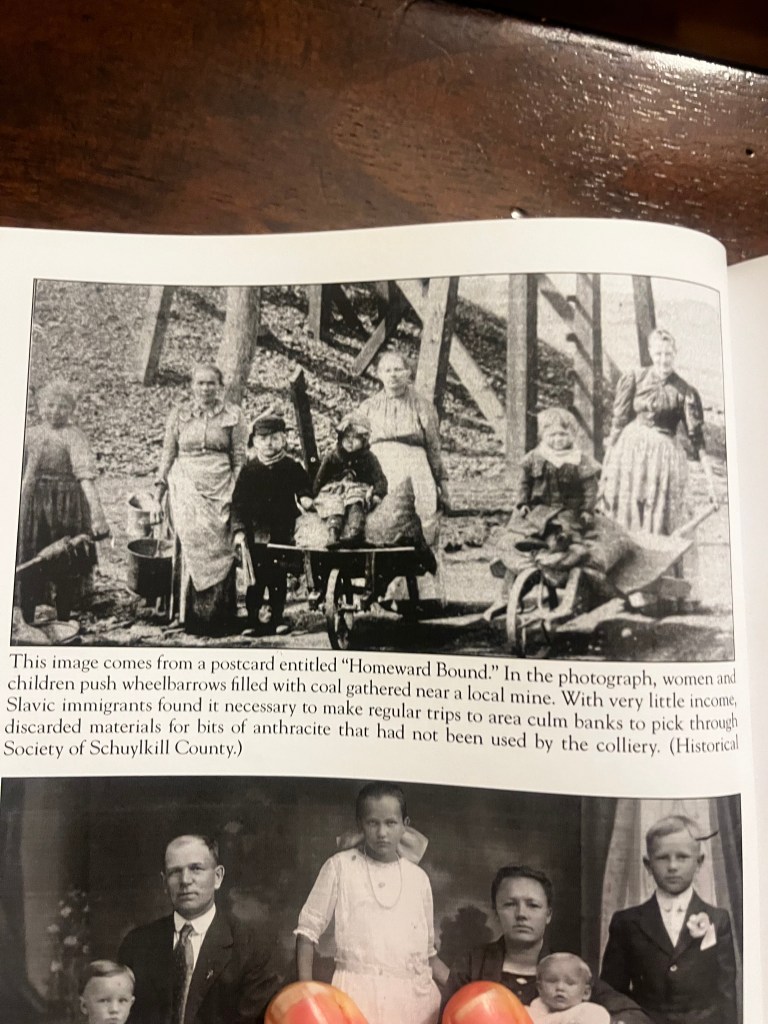

The Gorzynskis’ first stop in America was Glen Lyon, Pennsylvania where, in 1881, the wheelwright became a laborer for the Susquehanna Coal Company. The family photo suggests that Marian was tall. It’s an attribute he passed on. The men (and some of the women) in immediate family range in height from 6’0 to 6’7″. If Marian was anything over six foot tall, he probably found it challenging to work under ground.

Given his experience in carpentry, I imagine him as one of the men tasked with timbering tunnels.

Meanwhile, above ground, Great-Grandma Franciszka had babies. The miners were paid in scrip that could only be spent at company stores. There was never enough to feed a family, and it was the women’s job to figure out how to make it last.

Franciszka was the first of Thomas Gołembiewski’s daughters to leave home. She arrived in Castle Garden September 25, 1883, accompanied by an eleven month old daughter (Honorata). In July 1884, the couple’s eldest son Ladislas was born in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania. Later called Walter, he’s the boy standing between his parents in the family photo. My grandfather, Jozef, was born across the river from Nanticoke, in Plymouth, Pennsylvania on November 1, 1888. A daughter named Tekla was born in Pennsylvania in 1887. In 1890, their son John was born in Buffalo, followed by Helena, born in Buffalo in 1892. Their next son, Alfons, was born in Cleveland in 1894, and their final child, Ildefons (Edward), was also born in Cleveland in 1897. Looking at the photo, I calculate my grandfather is between six and eight. If that is so, then the baby is Alfons, the little girl in front, Helena.

Somewhere along the line, these folks earned a reputation that my father and his mother didn’t want to pass on. My siblings and I heard rumors about rum-running and organized crime. And one of grandpa’s migrant kin supposedly knew Leon Czolgosz, President McKinley’s assassin. I have researched that particular rumor in depth and come up with circumstantial evidence. The Górzyńskis lived five blocks away from the Czolgosz family. Leon worked at the same rolling mill each of the Górzyński men worked at one point or another. Leon’s father ran a bar not far from the rolling mills. Given my family’s love of drink, I’m sure my great-grandfather, my grandfather and his brothers visited it once or twice. Any association may have been passing. Does that deserve estrangement? If so, then every man who enjoyed a good drink and worked in the rolling mills was implicated.

I’m a member of Polish Genealogical Societies in both Cleveland and Buffalo, and I’ve met several Poles with ancestors who knew Leon Czolgosz or his family. Most retained their Polish name and identity. Not even Leon Czolgosz’s father took an alias. Marian and Franciszka didn’t change their names, either. But their children did. Shortly before World War I, America’s cities developed Americanization programs that targeted these immigrants’ children of immigrants. Recognizing their potential as soldiers and workers, these programs taught American culture. Cities with large immigrant communities continued those programs into the 1920’s. My grandfather may have resisted participating for a while, but my grandmother was ambitious. She went to business school, and she’d already changed her name once. She was the force behind their assimilation. After they changed their name, they left Warsawa behind. In 1932 they bought a home in Fairview Park, a semi-rural village on the west side of Cleveland. Then four years old, my father grew up there. If his Polish grandmother wanted to see her newest grandson, she needed to find someone who owned a car. Fairview Park probably seemed like another country to her.

My family history research has focused on restoring my migrant ancestors’ dignity, and their past. This blog does that. My novel The Double-Souled Son strives to do that, too, while also acknowledging these folks were probably far from perfect. The first part of the book recreates the Poland they left behind: a traditional village in its third generation of Prussian occupation where it’s getting harder to keep their Polish language and culture alive. Essentially, they were traumatized before they ever left home, and the conditions they encountered in America only made it worse. In the second part of the book, the characters remedy their alienation by recreating their village life in urban Polish enclaves. There, ancestors’ traditions were passed on to their children. How they came to America was integral to their identity.

The novel is fiction. The “real” story is slightly different. This photo represents a high point in my family’s journey towards building an American home. The “true” story I’ve cobbled together about it deserves to be told:

Based on my timeline, the Gorzynskis were living in Cleveland when they visited Pannebecker Photography, a well known shop in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania. Why did the family return to Pennsylvania?

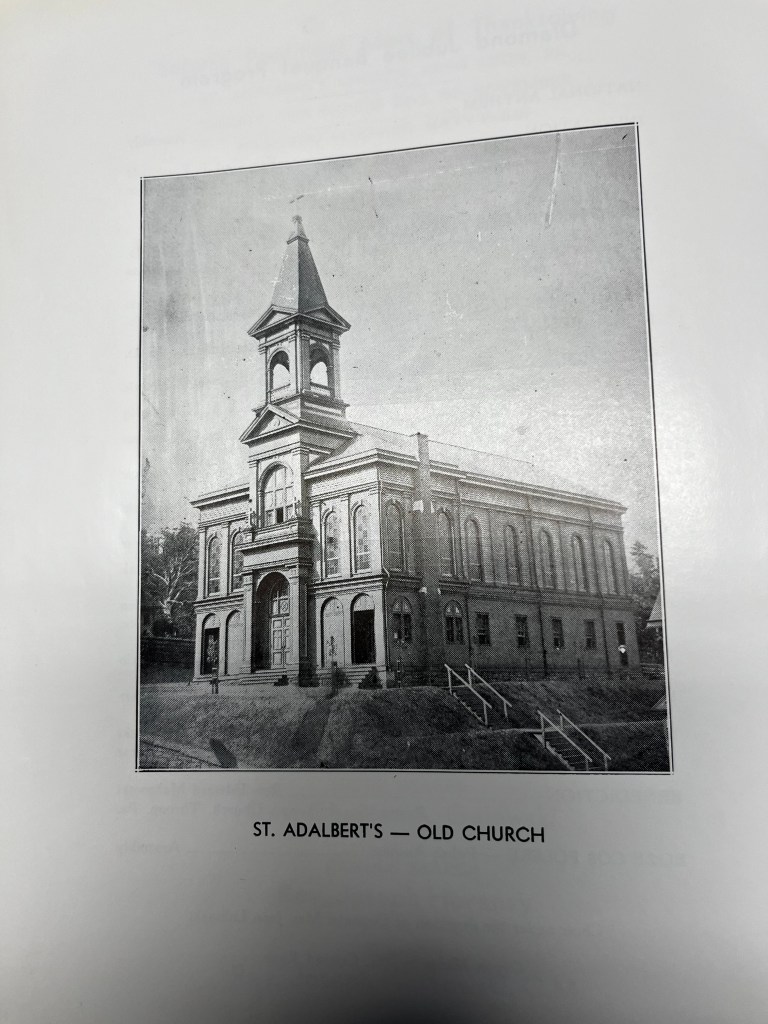

In 1939, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of St. Adalbert’s Roman Catholic Church in Glen Lyon, the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader published an article listing the names of the miners who founded that church, in 1889. On the fifth line from the bottom I found the name Marian Gorzynski.

Marian arrived in 1881. St. Adalbert’s cornerstone was laid 20 November 1889. Between 1881 and 1889, Glen Lyon’s Polish mine workers had to travel to Nanticoke’s St. Stanislaus if they wanted to attend a Catholic mass delivered in their own language. St. Adalbert Parish’s first service was held in a basement in 1889. The original church building was dedicated in 1891. My Gorzysnki family photo wasn’t taken then, though. Given my grandfather’s age in the photo, I’m imagining Marian and his family returned for a service inside the new church when they could finally afford to travel with all those children.

The family in my photo is far from silly. They’re happy. Perhaps for the first time since arriving in America, they’re proud. They’ve moved on to jobs that pay in United States currency, and they’ve saved enough of it to return to their first American home, and the church they helped build. This photo was a big expense for them. I’ll bet Franciszka made a new dress for it, and they surely had several copies made, one for each of their children, one for their own home, and one for Franciszka’s parents, who were still alive, living, in their home near the cross in Ostrowy.